Zhong Kui in Mythology

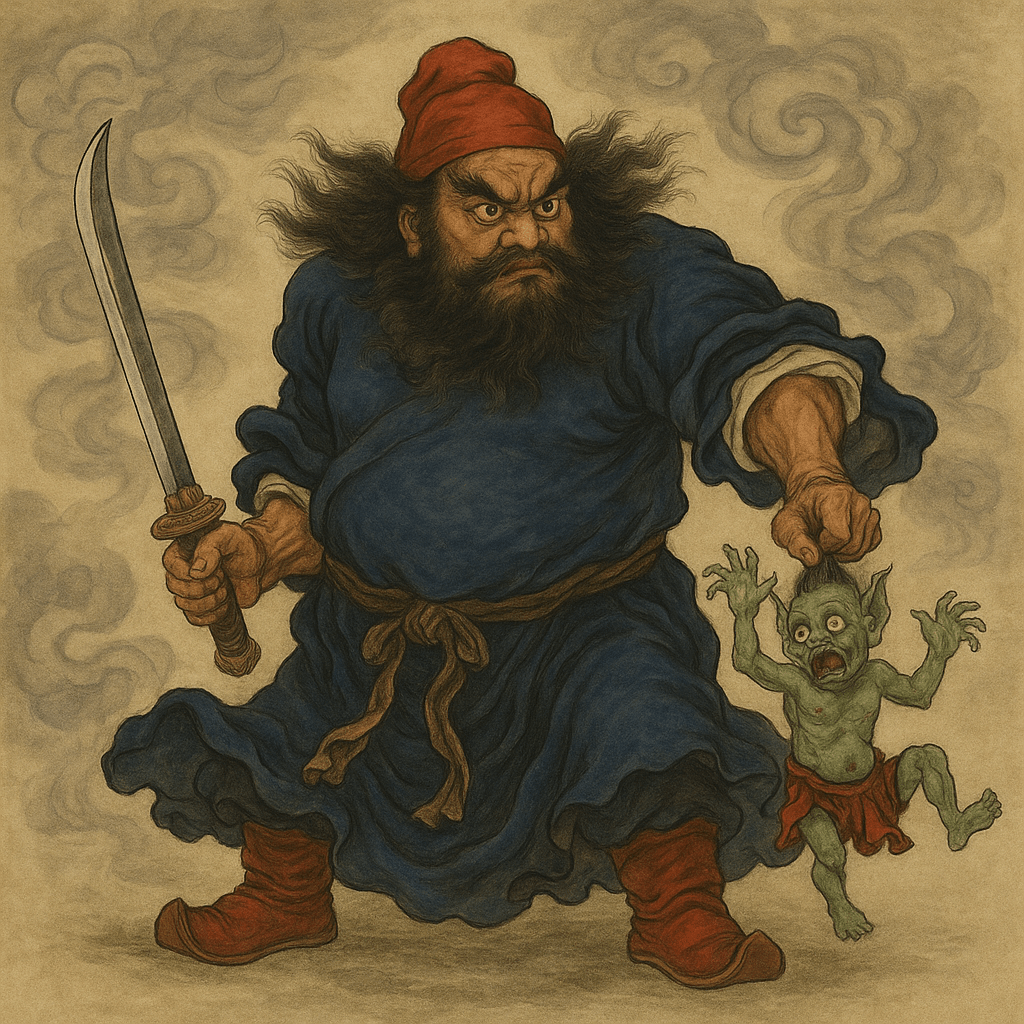

Zhong Kui (sometimes written as Zhongkui) stands out in Chinese mythology as a legendary demon-slaying guardian, often described as a fierce, ghost-catching figure. If you’re wondering who is Zhongkui, imagine a “ghostbuster” of ancient China – a deity entrusted with vanquishing evil spirits and keeping households safe. According to lore, Zhong Kui appears as a large man with a fearsome face: bulging eyes, a bristling black beard, and a no-nonsense scowl. Though terrifying to look at, he is fundamentally a force of good, roaming the realms to hunt down malicious ghosts.

The most famous myth about Zhong Kui involves a Tang Dynasty emperor and a life-changing dream. Legend says that Emperor Xuanzong of Tang fell gravely ill and dreamt of being plagued by a mischievous little ghost. In this dream, as the emperor watched helplessly, the impish specter stole a prized flute (in some tellings, even pilfering jewelry from the emperor’s beloved consort). Suddenly, a towering figure in an official’s cap stormed in. This giant grabbed the thieving ghoul, gouged out its eyes, and gobbled the demon down in one swift move. The impressed emperor asked the stranger his name. The fearsome figure bowed and introduced himself: Zhong Kui, a scholar who had met an unjust fate but now swore to protect the realm by ridding the world of evil spirits. When Emperor Xuanzong awoke from this vivid dream, he miraculously found his illness cured. Convinced the dream was a divine message, the emperor immediately commissioned his court painter (legend says it was the famous artist Wu Daozi) to paint Zhong Kui’s portrait exactly as seen in the dream. This first painting of Zhong Kui became a powerful talisman. The emperor displayed it in the palace to ward off further evil, and soon people all over the land began reproducing Zhong Kui’s image to keep their homes safe. Through this popular myth, essentially a royal endorsement from a Tang emperor’s vision - Zhong Kui earned his title as China’s ultimate demon queller in folklore.

Historical Background

One question many ask is whether Zhong Kui was a real historical person or purely a mythical creation. The consensus is that Zhong Kui is not a real, documented individual from history, but rather a legendary figure whose story evolved over time. The character likely amalgamates various folk beliefs and symbolic meanings. The earliest written record of Zhong Kui’s legend appeared in the Northern Song Dynasty (960 - 1127 CE), centuries after the Tang era where his story is set. A Song dynasty scholar named Shen Kuo included the tale of Emperor Xuanzong’s dream in his writings, suggesting that by the Song period the Zhong Kui legend was well known. In other words, historical texts portray Zhong Kui as a figure of folklore, not as an actual person who lived during the Tang Dynasty. There are no imperial records or biographies of an official named Zhong Kui performing supernatural feats; instead, his story was passed down as part of myth and oral tradition.

Interestingly, Zhong Kui’s origin story took on different embellishments as it traveled through the ages. One popular backstory (which became widespread by the Ming Dynasty) says Zhong Kui was originally a brilliant scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains in early Tang times. He supposedly earned top marks in the imperial examinations, but the emperor rejected him outright upon seeing Zhong Kui’s ugly appearance (described as dark-skinned, with a protruding forehead and wild beard). Devastated by this unjust humiliation, the scholar Zhong Kui took his own life on the palace steps. In some versions, the King of Hell took pity on Zhong Kui or admired his talent, and thus appointed him as the “King of Ghosts” in the underworld - assigning him the duty of catching wicked spirits to prevent harm to the living. Another variation holds that Emperor Gaozu of Tang (or in later plays, a loyal friend named Du Ping) gave Zhong Kui a proper burial out of respect, and in gratitude Zhong Kui’s spirit vowed to forever protect the emperor’s realm. These tales, though tragic, set the stage for Zhong Kui’s transformation from a wronged scholar into a demon-slaying deity.

Over the centuries, scholars have also offered intriguing theories about the name “Zhong Kui.” Some trace it back to antiquity: during the Zhou or even Shang dynasty eras, “zhongkui” was the name of a demon-exorcising tool or ritual mallet. It’s possible the folk hero inherited this name to signify his demon-banishing role. Others point to classical medicine and folklore - for example, Ming-era herbalist Li Shizhen noted a type of mushroom called “zhong kui” which was used to treat malaria (a disease once thought to be caused by evil spirits). In that light, naming a deity Zhong Kui symbolized a cure for demon-caused illness. Another Ming scholar suggested Zhong Kui might have been inspired by a real historical figure: a Northern Wei Dynasty governor whose nickname was Bi Xie (“warder-off of evil”). While it’s hard to prove direct links, these theories show how people have tried to root Zhong Kui in cultural context, connecting him to older traditions of protecting against harm.

As time went on, Zhong Kui’s image evolved with each dynasty’s artistic tastes and religious beliefs. By the Song and Yuan periods, writers described him as a powerful ghost rather than a god - specifically, a “big ghost” or “ghost hero” who nonetheless acted with divine authority. In popular imagination, however, Zhong Kui was essentially deified as a guardian spirit. Unlike many gods, he never had an official state cult or grand temples; instead, his “altar” was the artwork and talismans people hung in their homes. Ming Dynasty lore even highlights this uniqueness: in one play, Zhong Kui wryly remarks that he has no dedicated festival or regular offerings, yet humanity’s faith in his picture alone gives him the strength to keep battling demons. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, Zhong Kui had become a beloved fixture of folk religion. Mass-produced woodblock prints of the demon queller were common, especially as New Year decorations. He was consistently depicted as a formidable Tang-era scholar-official, complete with a flowing robe and an official’s black cap - imagery derived from that lost Tang painting and subsequent artistic tradition. One constant feature in every era was his bushy beard, so iconic that people gave him nicknames like “Old Beard” and “Bearded Lord”! Having a robust beard in Chinese culture traditionally symbolized vitality and vigor, so this trait underscored Zhong Kui’s power to ward off sickness and evil.

Zhong Kui’s influence wasn’t confined to the mainland either. The legend crossed the sea to Japan, where he is known as Shōki. In Japanese folklore and art, Shōki the demon queller became popular as well, often invoked to ward off epidemics and evil, especially during the Boys’ Day festival. This cross-cultural adoption further cements Zhong Kui’s status as a timeless emblem of protective power in the East Asian world.

Folk Beliefs

As a folkloric guardian, Zhong Kui figures prominently in everyday folk beliefs and practices in Chinese communities. Perhaps the most widespread custom is to display images of Zhong Kui in the home to keep evil at bay. Even today, many families hang a painting or print of Zhong Kui above their front door or in the main hall as a protective talisman. With his glaring eyes and sword in hand, Zhong Kui’s portrait is believed to frighten away wandering ghosts, malevolent spirits, or any forces of bad luck. This practice is especially common around Lunar New Year, when households want to start the year on an auspicious note by barring entry to any ill-fortune. In effect, Zhong Kui acts as a fierce spiritual bouncer for the home - a role similar to that of door gods in Chinese tradition, and indeed some consider him a type of door god himself.

Beyond passive pictures on the wall, Zhong Kui also comes alive through exorcism rituals and performances. For centuries, temple priests, shamans, and even laypeople have invoked Zhong Kui’s name during rites to expel evil. In some ceremonies, a priest might hold a sword or a wooden plaque inscribed with Zhong Kui’s likeness, commanding troublesome ghosts to depart. One dramatic folk ritual known as “Dancing Zhong Kui” (跳鍾馗, tiào Zhōngkuí) showcases just how literally people embody this deity. In this tradition – still observed in parts of Taiwan and southern China - a performer or spirit-medium dresses up as Zhong Kui, complete with a ragged robe, a black cap (or sometimes a broken scholar’s hat), and face paint to look as fearsome and red-faced as the demon queller himself. Wielding a sword and other exorcism tools, the impersonator staggers and leaps about in a trance-like dance, as if Zhong Kui’s spirit has descended. They perform startling tricks believed to scare away demons - breathing fire, brandishing the sword, even mock sword-swallowing or other feats - all to the gasps and cheers of villagers. This “Jumping Zhong Kui” ritual is often carried out during times of communal need: for example, to cleanse a new house or a temple, to drive away lingering spirits after a funeral, or at festivals associated with ghostly activity. It’s not always a somber affair; depending on context, a Zhong Kui dance can be part of a lively celebration (such as inaugurating a new temple or during a local festival) to bring good luck and dispel any lurking evils in a jubilant way. Through these folk practices – from the quiet hanging of a doorway portrait to the loud spectacle of an exorcism dance – Zhong Kui continues to be an active presence in daily spiritual life, a go-to guardian whenever people seek protection from unseen forces.

Zhong Kui in Art and Literature

Zhong Kui’s fearsome yet righteous character has inspired countless works of art, literature, and performance in Chinese culture. In visual art, he is a favorite subject for painters across the centuries. Traditional paintings often portray Zhong Kui in vivid scenes: for example, storming through the night on a demon-hunting patrol, armed with his sword, with a cadre of little demons already captured and cowering at his feet. Some artworks show a more humorous side - a famous motif is “Zhong Kui Traveling with His Sister,” or “Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister,” which depicts the demon queller acting as a protective big brother escorting his beloved younger sister (in these images, terrified little devils carry the sister’s bridal sedan or luggage, making for an amusing contrast between Zhong Kui’s grim duty and a joyous family occasion!). These themes come from folk tales where Zhong Kui, despite his gruesome job, cares for his family’s happiness. Such paintings were popular in the Ming and Qing periods, blending supernatural drama with touches of comedy and humanity. Artists usually rendered Zhong Kui with exaggerated features - the better to convey his scary appearance - but often with rich color and detail that made these paintings auspicious decorations. Aside from high art, folk prints and New Year pictures of Zhong Kui have been mass-produced since at least the 10th century. Brightly colored woodblock prints of Zhong Kui would be pasted up during festivals to ward off evil; many of these show him in mid-action capturing ghosts, or simply standing guard with a menacing posture. These artistic depictions helped cement the standard image of Zhong Kui in people’s minds: a stout, scowling man in scholar-official robes, often wearing a red garment for emphasis, and always ready to battle demons. In some paintings he even stands on a demon or has bats flying around him (bats being symbols of good fortune, homophonous with “blessings” in Chinese - a clever visual pun indicating that Zhong Kui conquers evil and brings blessings).

Literature and opera have also kept Zhong Kui’s legend alive. Storytellers through the ages have written countless folk tales, operas, and plays featuring Zhong Kui. During the Ming dynasty, for instance, writers incorporated Zhong Kui into popular theater plays. One play by writer Zhu Youdun, as mentioned earlier, has Zhong Kui comment on his unusual godhood (no formal worship, yet widely revered through images) - showing that even in literature, people found his case interesting and unique. In the Qing dynasty’s famous anthology of supernatural tales, it’s said that Zhong Kui occasionally gets a mention as well - unsurprising, given his role as chief ghost-buster. Perhaps most enduring is Zhong Kui’s presence in Chinese opera, particularly Peking Opera and regional operas. He is typically cast as a “jing” role (painted face male role) or sometimes a “wusheng” (martial hero) because of his brave, action-oriented character. On stage, Zhong Kui is hard to miss: the actor will don a fierce-looking mask or face paint, usually with a blue or black base and bold designs to accentuate a scowling, wrathful expression, along with an attached long beard. He wears a costume resembling a court official’s robe, and often carries a prop sword. One very popular opera piece that is still performed is “Zhong Kui Marries Off His Sister.” In this story (drawn from those folk tales and artworks), Zhong Kui arranges a marriage for his sister to a mortal man (often his friend Du Ping) to ensure she has a normal, happy life. The opera combines action - Zhong Kui battling and commanding demons to safeguard the wedding procession - with comedy and warmth as a contrast between the terrifying demon-slayer and domestic concerns. Audiences have loved this piece for generations, as it shows a softer side of the ghost hunter without diminishing his supernatural prowess. Beyond this, Zhong Kui appears in other operatic stories dealing with exorcism and justice, reinforcing his image as a cultural symbol of righteous power.

In literature, Zhong Kui’s name even finds its way into idioms and sayings. For example, Chinese speakers might jokingly say someone is “inviting Zhong Kui to catch a ghost” (打鬼借鍾馗) to describe making a big effort for something that turned out trivial – a phrase inspired by the idea of using a cannon to shoot a mosquito, or rather, summoning a mighty demon queller to tackle a minor nuisance! Another saying describes a person who is outwardly ugly but good-hearted by comparing them to Zhong Kui (hinting that despite his fearsome visage, he uses his strength for benevolence). These linguistic nods show how deeply ingrained Zhong Kui is in the cultural imagination. Whether in fine art, popular woodcuts, gripping theater, or everyday language, Zhong Kui has been depicted and celebrated from ancient times through every era of Chinese art and literature.

Festivals and Customs

Throughout the year, certain traditional festivals and seasonal customs shine an extra spotlight on Zhong Kui, underscoring his role in safeguarding people from harm. Here are a few notable examples:

- Chinese New Year (Spring Festival): As the new lunar year approaches, families clean their homes and put up auspicious decorations - and it’s common to include Zhong Kui’s image as part of this ritual. On New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day, a portrait of Zhong Kui might be hung near the door to prevent any negative spirits from entering in the year ahead. The Lunar New Year is all about driving out the old bad luck and welcoming good fortune, and Zhong Kui, with his demon-expelling prowess, is the perfect guardian for this occasion. His fierce figure at the threshold is believed to stop demons or bad luck in their tracks, ensuring only good vibes cross into the home as the year begins.

- Dragon Boat Festival (Duanwu Festival): This festival falls on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month (usually June in the Gregorian calendar) and is known for its dragon boat races and rice dumplings. Historically, the summer months were regarded as a time when illness and pestilence could spread (in ancient terms, “evil spirits” of disease). Thus, Duanwu evolved with traditions to dispel negativity and invoke protection. Zhong Kui is closely associated with the Dragon Boat Festival as a potent talisman against summer epidemics. In many regions, people will hang up Zhong Kui pictures or paper cutouts during this period – often alongside bundles of mugwort and calamus (medicinal herbs) - to ward off the so-called “Five Poison” pests and any demons of sickness. There’s even a saying that having Zhong Kui’s image displayed during Dragon Boat Festival protects the household from the “evil vapors” of the hot fifth month. So as families enjoy zongzi (rice dumplings) and race dragon boats, they also remember Zhong Kui’s watchful presence keeping the mid-year dangers away.

- Ghost Festival (Zhongyuan Festival): The Ghost Festival is observed on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month (usually in late summer). It’s a time when, according to folklore, the Gates of the Underworld open and spirits roam freely among the living. People make offerings to honor ancestors and appease lonely ghosts during this month. While much of the Ghost Festival involves showing respect and feeding the spirits, there’s also an element of caution - not all wandering ghosts are friendly. Enter Zhong Kui: he becomes a symbolic figure of authority who can keep unruly or harmful ghosts in check. In some locales, particularly in Taiwan, the end of Ghost Month features ceremonies to send the ghosts back to the underworld. One such ritual is nicknamed “Jumping Zhong Kui”, where (as described earlier) priests or volunteers dress as the demon queller to ritually “catch” any remaining mischievous spirits before the gates close. This end-of-festival exorcism underscores the idea that Zhong Kui patrols the border between the living and spirit worlds, rounding up stragglers and restoring order. Even if a full-on performance isn’t held, people might still invoke Zhong Kui’s name or display his picture during the Ghost Festival as a protective charm, just to be safe. In short, whenever ghosts are about, folks like to have Zhong Kui around!

Throughout these festivities - whether it’s welcoming a new year, guarding against summer diseases, or minding the ghostly population - Zhong Kui’s legend is woven into the seasonal rhythms of Chinese culture. His fierce image and story give people confidence that they have a powerful ally watching over them during these important times of year.

Zhong Kui in Modern Culture

Thanks to his iconic status, Zhong Kui continues to find new life in modern media and popular culture. In recent years, one of the biggest boosts to Zhong Kui’s global profile has come from the world of video games - specifically the highly anticipated Black Myth series by Chinese developer Game Science. Following the massive buzz and success of Black Myth: Wukong (an action-RPG based on the Monkey King Sun Wukong), the studio announced a new Black Myth game centered on Zhong Kui. This upcoming title, Black Myth: Zhong Kui, instantly grabbed attention. Gaming fans around the world, many of whom were introduced to Chinese mythological heroes through the Wukong game trailers, are now excitedly asking, “Who is Zhongkui?” and eager to see what adventures the Zhongkui game will offer.

In Black Myth: Zhong Kui, players will get to step into the boots of the legendary ghost-catching god himself. Early teasers and the official announcement (revealed during a major gaming event) describe Zhong Kui as a warrior who “wanders between Hell and Earth” hunting spirits - a perfect encapsulation of the classic folklore image, now brought to life with cutting-edge graphics. The game is set to be an action role-playing experience, much like its predecessor, blending intense combat with rich storytelling drawn from mythology. It’s the second installment in the Black Myth series, and although details are still emerging, the mere news of Zhong Kui as the protagonist has reignited global interest in this ancient character. Gamers who loved the mystical world of Black Myth: Wukong (some even dub it “Black Wukong”) are thrilled to see Game Science expanding the franchise to showcase another pillar of Chinese legend.

What’s remarkable is how this modern interpretation is turning Zhong Kui into a pop culture figure beyond Asia. For a long time, Sun Wukong (the Monkey King) was arguably the most internationally recognized character from Chinese lore, thanks to countless adaptations. Now, with Black Myth shining a spotlight on Zhong Kui, the “Black Zhongkui” is stepping onto the world stage. Discussions online have people trading snippets of Zhong Kui’s backstory, drawing fan art of the demon queller, and comparing notes on Chinese mythology. Even other games have featured Zhong Kui before (for instance, the myth-themed game SMITE included Zhong Kui as a playable character), but never with this level of realistic detail and narrative focus. The Black Myth: Zhong Kui project indicates a broader trend: Chinese mythology is becoming increasingly influential in global entertainment. As we await this new game’s release on PC and consoles, there’s a growing appreciation and curiosity about Zhong Kui’s lore. It’s a fantastic example of how an ancient legend can be reborn for a new generation, with the help of high-tech storytelling. The ghost hunter who once appeared only in dusty tales and paintings is now poised to slash demons on our screens in spectacular fashion – truly a modern journey for our demon-slaying hero.

Zhong Kui in Jewelry Design

Beyond games and festivals, Zhong Kui - along with other mythological icons like Sun Wukong - has even found his way into the world of modern jewelry design. In recent years, some innovative jewelers have started reinterpreting famous folklore figures as wearable art, creating pieces that celebrate cultural heritage in a contemporary style. It’s part of a broader movement to infuse jewelry with deeper storytelling and symbolism, rather than just using abstract designs. For example, a pendant or ring might feature Zhong Kui’s distinctive likeness - perhaps a small carving of his fierce face or him brandishing a sword - allowing the wearer to carry a symbol of protection and courage wherever they go. Similarly, the Monkey King Wukong might be depicted with his magic staff on a bracelet or necklace, representing rebellion and wit. These myth-inspired pieces resonate especially with young Chinese consumers and collectors worldwide who want to stay connected to their roots in a stylish way.

What makes these designs truly special is the emphasis on cultural symbols, traditional techniques, and meaningful materials. Jewelers are not simply slapping mythic figures on ornaments; they are thoughtfully embedding heritage into their craftsmanship. Many draw on traditional artisanal techniques passed down through generations. You might find evidence of ancient metalworking methods, like intricate filigree patterns or hand-engraved motifs of clouds and auspicious creatures, in a Zhong Kui-themed piece. Some designers incorporate rare, meaningful materials - for instance, genuine jade or other gemstones that carry symbolism in Chinese culture. Jade, often associated with purity and protection, is a fitting choice for a Zhong Kui amulet, enhancing the idea that the jewelry isn’t just decoration, but a modern-day talisman. Others might use unique woods or metals tied to legend (imagine a inlay of fragrant cedar or sandalwood, which were used in old amulets, or accents of bronze and gold to echo ancient ritual objects). The result is wearable art with a story - each piece invites the wearer to remember the values and tales of figures like Zhong Kui and Wukong, blending fashion with folklore.

Notably, some artisan brands have made it their mission to bring these cultural elements to the fore. For instance, brands like Zodori prioritize bringing heritage craftsmanship and rich symbolism into contemporary, meaningful jewelry. Such designers treat jewelry-making almost like storytelling. When crafting a Zhong Kui-inspired item, they ensure that every element - from the carving style to the materials - honors the original legend and the culture it comes from. The fierce expression of Zhong Kui might be rendered with the same attention to detail as in a classical painting, and the piece might be blessed or debuted during a festive occasion for added authenticity. By doing so, modern jewelers transform mythological characters into personal keepsakes, allowing people today to literally wear a piece of their heritage. Whether it’s a Black Myth Wukong fan sporting a Monkey King necklace or a culture enthusiast wearing a Zhong Kui bracelet for luck, these creations keep ancient heroes alive in our daily lives. In the hands of creative designers, symbols of Zhong Kui and his peers transcend stories and become tangible connections to tradition - tiny treasures that carry the spirit of legends into the modern world.